|

Hauptseite

Sitemap

- Physik

- Asteroidenabwehr

- Dunkle Energie

- Dunkle Materie

- GAIA-Milchstraße

- Sternschnuppen

- Quiz: Astronomie

- Genauigkeit

- Große Zahlen

- Erdmagnetfeld

- Pyramidenbau

Energie:

- E-Speicherung

- Solar I

- Solar II

- Fluss-Strom

- E-Bergwerke

- Gesamtkonzept

- Verkehr

- Blinken

- Spritsparen

- Gesund

- Erkältung

- Mikro-Inhalation

- Fersensporn

- Rücken

- Langsam

- Intervallfasten

- Vorhofflimmern

- MHD

- Koffein-Sucht

- Spiel

- Quiz: Rechnen

- Quiz: Geographie

- Quiz: Astronomie

- Irrgarten

- English

- Pronounce

- Asteroid Deviation

- Dark Energy

- Dark Matter

- Autobiography

- Vermischtes

- Commodore

- CBM 8028

- Verschlüsselung

- Freier Wille

- GPT-Träume

- Link-Tipps

- Musik-Links

- Talente

- Bewerbung

- Bizarr

- Astrologie

- Pfui Tracking

- Soziale Netzwerke

- Rechtschreibung

- Lehrer

- Tortraining

- Langsam

- Eiscreme

- Matterhorn

- Marie

Letzte Änderung / Last update: 2025-Jun-22

|

Pronunciation of the German Language

|

When you come across a German text or just a name, and you want to pronounce them correctly, without causing confusion among German listeners, these hints here might be helpful to you. There are many similarities, but also some severe differences, where it is often astonishing for Germans, that Americans never seem to have heard about the issue. So here you get some enlightenment. By the way, here we do not need to take differences between British and American English into consideration, this might only come up in very special cases. German as another European language is definitely closer in pronunciation to British English than to American English, and at school, a German pupil (never "student", which is reserved for university visitors) also first learns British English, as they are practically direct neighbours, only parted by some North Sea water. In general, German is considered a "mostly phonetic language", i.e. a language where you can easily derive the pronunciation from the spelling. Nothing is perfect, though, there are still exceptions. Yet definitely much fewer than in English. To increase the quality, you should discern the diphthongs, tell the original German words from some imported loan words, which often follow their original pronunciation. (In this regard, German is more flexible than e.g. French, where much more terms are strictly submitted to French pronunciation rules.) Then you are on a good way. Please note that in the relatively recent past Germany consisted of dozens of smaller or bigger kingdoms, all with their own deliberately chosen individuality, especially in terms of accents and dialects. Those differ often from one village to the next one over the hill, to such an extent that people just do not understand one another. Modern communication media have settled this to some degree, but still you have to cope with highly varying accents. — Let alone really different languages within the German borders. Near the borders to the many different neighboring countries with their different languages, this is quite common. But then there is also the sorbische (Sorbian) language, a Slavic dialect on its own spoken in a region bordering Poland, however differing strongly from Polish. Or up in the north, we have the friesische (Frisian) language, which is in fact some Gaelic variety. This also is the region called Angeln, and now you know where the term "Anglo-Saxon" comes from: from this Angeln and from the Saxons (German "Sachsen") a bit farther down south and a bit east. — And do not even mention Swiss German: An ordinary German can hardly understand any word of Swiss-German TV news, where they are not supposed to speak with a strong accent. Now guess what happens out in remote rural Swiss areas. Basically, this text is about the pronunciation of single letters, plus some cases of diphthongs and some such. A general issue with German pronunciation is that words are normally not linked to the following one when speaking, as opposite to the uses in English or also in French. This does not mean you are supposed to speak in a staccato style, you just need not make any effort to bind the words together. (Of course, in the case of words printed together, which is a major feature of the German language, then you also pronounce them accordingly.) By the way, there's a very special place for Americans to learn or practise the German pronunciation: Hawaii! As the story was told to me, there was a German monk, who lived on Hawaii and who was the first one to attempt to find a way to write down the original Hawaiian language. Being a German, he simply used the pronunciation rules he knew from his old country. So Hawaiian was written down in a way to be pronounced like an ordinary German text. Today, you can still experience that without really being able to speak the Hawaiian language: The names of places and mountains can already be pronounced properly. So, if you see names like Oahu or Haleakala or Halemaumau, just use the hints given here to pronounce them, and you will sound like a real Hawaiian insider. Then you will find, that the often attached hints for pronunciation or phonetic transcriptions into American English are less perfect, as they do not eliminate some of the pitfalls especially with regard to the pronunciation of vowels. Plain text here is to be read as an English text with English pronunciation. When a text is printed in italics (Schrägschrift), it is supposed to be a German text in German pronunciation. Here we will mainly discuss Hochdeutsch, or High German, the standard German way of writing and speaking. The variation of local dialects within Germany is much higher than in the USA, I think. In Britain, with its Gaelic portions (which have close relations to northern German Frisian regions) and Scottish varieties, cases are comparable, though. A hint concerning web links, if you read this text printed on paper and cannot directly click on the provided links: For a Wikipedia link [en-WP xyz] or [de-WP xyz] (en or de, respectively, mark the English or German language version of Wikipedia), type the text after the key word WP into the search field at the top of any Wikipedia page, and so you get to the desired page. — The same is valid for YouTube videos and their key word YT. — A third place which is often linked to is de.forvo.com. Here you type in a German word and forvo will present you with one or several audio samples from native German speakers pronouncing this word. This is a very reliable source of realistic sounding speach.

1. Overview

Let's view the whole alphabet and first sort out the easy cases, where there is no significant difference between German and English pronunciation.| Letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J |

| Difference | V | = | C | = | V | = | G | = | V | C | Spelling | Ah | Beh | Tseh | Deh | Eh | Eff | Geh | Hah | Ie | Yot |

| Letter | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T |

| Difference | C | C | = | = | V | = | C | C | C | = | Spelling | Kah | Ell | Emm | Enn | Oh | Peh | Kuh | Err | Ess | Teh |

| Letter | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Ä | Ö | Ü | ß |

| Difference | V | C | C | C | C/V | C | V | V | V | C | Spelling | Ooh | Fow | Veh | Iks | Ypsilon (Ypp-see-lonn) |

Tset | Äh | Öh | Üh | Ess-tsett |

2. Consonants

Here are found only few differences, some of them not really a problem, but nonetheless why not try to do it even a little better. Let's work through the cases one by one:| C | In English, the C can stand for a K sound (like in car), or for a sharp S (like in ice). In pure German, without foreign lean words, C hardly occurs alone, normally only in diphthongs like ch, ck, or sch. In the rest, it stands in most cases for a TS sound, but sometimes can also stand, like in English, for a K sound. Both is found in the German pronunciation of the word circa, which is pronounced like TSIRKAH (listen to forvo, click on a blue triangle to start the sample). Hardly ever, the C is pronounced like a sharp S, some foreign imported words may serve as an exception to support the rule. |

| G | In English, the G can stand for a soft sound DSH (like in the word general, dsch in German) or for a hard sound like in the word gold. In German, only the latter variant is used. Foreign lean words may again serve as exceptions. — A special case is the letter combination IG (does this count as a diphthong? I don't know) at the end of a word or syllable. This is often, varying regionally, but not always, turned into a ICH (for the CH diphthong, see below). A good example is the word richtig (right, listen to forvo, where even these two variants are presented). |

| J | The standard English pronunciation would be represented by a dsch sound in German. But this occurs in German only in some not representative northern dialects, not in high German. The normal pronunciation is similar to the Y in the English word yet. Example is the word jung (young, listen to forvo). Like in English, the J sometimes is not distinguishable from an I in some combinations. |

| K | Well, the K itself is pronounced the same in both English and German. Yet in English, it is sometimes silent, like in the words knee or know. But in German, it is also clearly pronounced in these cases, like Knie (knee, listen to forvo), Knall (bang), Knopf (button), or a related verb like zuknöpfen (close a clothings button). |

| L | This is, similarly to the R below, a case, where the English and German pronunciations are basically equal, but there is a heavy difference in intonation, in the details, how this sound is formed in your mouth. In English pronunciation, your tongue tends to bend/curl backwards a bit while forming the L, like it's more expressively occuring in Spanish. Whereas in German, you leave your tongue flat straight out, which produces a more dry sound. As said, it's not much of a difference, but instantly audible, and if you want to sound more like a German, then you better care for this. Example is the word allein (alone, listen to forvo). — Another issue is a doubled L. Unlike in French or Spanish, a double LL in German still always sounds like an L and does not convert into a Y (or J, see above). |

| Q | In English, the Q mostly occurs in the QU diphthong, pronounced as KW (with English W, see below), and in some cases like a K. In German, it's also the diphthong KW, but with the German W (see below), so together more like an English KV sound. Example is the word Quelle (source, well, listen to forvo). A pronunciation as K is not known to me in German, but some imported word might be the exception. |

| R | This is like the L, but much, much harder. When you want to detect an

Englishman or American trying to speak like a German, this is one of the

big stepping stones. The intonation is sooo different! When I, as a German,

want to produce an American R, I have to draw back my tongue, stuff it back

deep down into my throat and groan like a lion. Yes, it's such stressy for

us! To me, the German pronunciation appears so much easier and lazier.

Yet I suspect, the other way round it will be exactly the same... Now, how

to intonate a German R? For this you leave your tongue stretched

out flatly, get its tip shortly behind your nearly closed lips and then

loosen the tongue muscles, so that it can flutter up and down in the

stream of air: RRRRRRRR. Only the frontmost 5 millimeters of your

tongue are fluttering. (Do NOT ask experts about this issue: They will tell

you, no, it's just the other way round, American R pronounced at the front

of your mouth, and the German R back down in your throat! I call bullshit,

don't believe them a word.) Ok, to be precise, this is the stressy,

laborious version, which occurs for R's inside or at the start of

words. An example is the word Radio

(listen to forvo).

At the end of words, however, we can celebrate one of the few

moments where German is more lazy and comfortable to pronounce than

other languages, like English: Here, at the end, the R in German degenerates

to some simple, groaned AH, with the voice toning down a bit. And it's also

often very short. For example, the German word er (English: he,

listen to forvo) sounds

like an English EH-AH, with a dark and short AH (see also about vowels below).

— Another hint: When you know the Scottish dialect, their R seems rather

similar to the German one, I think. (At least some Scottish colleague

at work sounded that way, but there it's much more explicit and rough,

the German one is much softer.) But there are two regions in Germany where they practically use the American R: Oberlausitz (far east of Germany) and Wetterau (north of Frankfurt on the Main), yet they are not at all representative for the rest. |

| S | In English, the S alone is normally pronounced as a sharp S, you have the Z for a soft S sound. That's different in German. Here, the S can stand both for the sharp as well as the soft S, and there's no simple rule to tell one from the other. You have to learn it by heart for each word, sorry. |

| V | In English, the V is normally a rather soft sound like in the word very. In German, it's in most cases a sharp sound, identical to the F. There are example sentences for German pupils to teach them the spelling differences: Viele Vögel fielen vom Baum (many birds fell from the tree). All V's and F's pronounced equally. Some foreign lean words like Variation serve again as exceptions, pronounced with the soft sound, but they are not original German words. |

| W | To reproduce the English pronunciation, Germans often write something like UOTT (for the word what). The German pronunciation is simply the same as the English one for the letter V. |

| X | The English pronunciation is often like a GZ, rather soft: Xanadu. In German, the X is always pronounced like KS, like in the English words text or exit. |

| Y | The letter Y is in both languages a double issue: It's normally listed among the consonants, sounding in English like the German J (like in the word yet). In other occasions, it serves as another vowel, replacing the I or, in German, sometimes also the Ü, see there. In this consonants section, let me repeat that the Y is pronounced very much like the German J. The letter is read out as Ypsilon (listen to forvo). |

| Z | In English, the Z stands for a soft S. Only in diphthongs like TZ it sounds sharp. This diphthong is just the same in German, but the Z alone is just the same sharp sound, here. It's like a TS sound, with a sharp S, or just like the already mentioned TZ diphthong. In German, there's no difference between Z and TZ. An example is the number 10, zehn (listen to forvo), pronounced like TSEHN with a light E. By the way, in Italian it's rather similar to German in this regard. |

| ß | This is in German the sharp S, its other name being Eszett (with

that sharp Z sound, like ess-tsett). As an English speaking person, you

don't know this letter at all.

If a bit literate, you may identify it as a greek beta. But it's not that.

It's totally different, has nothing at all to do with it. NOTHING.

It just looks very similar, but in high-resolution fonts you will find

differences.

(Please excuse me getting loud, but I can tell you about the hazzles, when

I sent my American colleagues some text by fax (long, long ago) to include

on some packaging or so, and they replaced all ß's with lower case b's!

Because they thought, hmm, that's a beta, we don't have a beta on our (8-bit,

early 1980's) computer, we gonna replace the greek beta with its latin

equivalent b. Boom, bang, crash. Oh boy.) So, if you're interested in the

history of this special letter, look around under

[de-WP Eszett] (S-Z) or

scharfes S, e.g. in the German Wikipedia, or also in

[en-WP Eszett].

So in the end, the ß serves as a sharp S, nothing else,

no problem to pronounce. — There are more issues with it: It has no

uppercase variant! At least in older, normal German, Unicode begs to differ, see

also the link above to the German Wikipedia article. And very recently,

it has also got official support, but it still is hardly used. So nobody

I know uses it, no person, no publication, so we have to live with it.

So when you convert a text to uppercase, you have to replace it by a double

SS. (So this is a nightmare for programmers, who sometimes have to convert

text between lower case and upper case: One direction is easy, but then

there's no way back! Not every SS stands for a capitalized Eszett,

a double ss is also very common.) — This is also the rule (not to be violated,

see below, by capital punishment!) when you don't have an ß available on your

keyboard: Replace it by a double SS (or ss), NEVER only by a single S and

also NEVER EVER by a b! (Sorry again for the loud tone.) —

Another issue of the Eszett is that it is practically abandoned in Swiss

German: There it is routinely transcribed either into SS like told above,

but some people there also transcribe it into a SZ. So better watch out. Yet back to pronunciation: The ß can serve to determine the pronunciation of the preceding vowel: An ß only comes after a long vowel or a vowel diphthong like au or ei. A double ss comes after a short vowel. Example: The German word Maß (general measure or a 1-liter beer glass) is pronounced with a long AH, where the German word Masse (mass) is pronounced with a short A. |

3. Vowels

First, in general, German vowels (and their umlauts, see below) are pronounced strictly straight and constant. No diphthongs like in the English A (in German spelling, that English pronunciation would look like Ä-I). A German A is not such a diphthong, but a constant AHHHHHHH.About Light and Dark Vowels, or Closed and Open Vowels. You know perhaps about the accents in French language. An accent aigu on an E (é) marks it as a light e. This sound does not exist in English, and it's one of the most horrible situations when an American tries to reproduce that (do you know the Champs Elysées in Paris? Ouch. This is often soo totally, absolutely, cruely, evily wrong pronounced!). Often, it degenerates into some diphthong like aye, but I already told you, there are no diphthongs in the pronunciation of single vowels, period. (About written diphthongs and their pronunciation, see below.) As Europeans, we simply cannot understand where there's a difficulty producing this sound, for us it's easy. (Compare that to the injuries of our tongues we risk during learning to pronounce your TH.) There are closed and open variants of some of the vowels, not all. Affected are E, O, and O-Umlaut. The principle difference between closed and open vowels is in your lips. When you keep them nearly closed or keep them wide open, that makes for a difference. Closed here means a decreased width of your lips opening, only about half of the full width. For first steps, you can try to tip your lips like for kissing or for the word boot, but afterwards this is not necessary anymore, just close the sides of your lips. Here come the vowels:

| A | In German, this is a straight AHHH. Perhaps similar to the U in words like fun or gun, or like the OU in the word double, or like the A in the English word barn. Example is the word Banane (listen to forvo). |

| E | In German, there is the light E, like the French é; and

there is the dark E, like the French è, the latter very similar

to the umlaut Ä (see below), also occuring in English (like in the word

bed). An example is the word Ente (duck,

listen to forvo).

So the dark/open variant shouldn't be any problem for an English speaker. To produce the light E, the main issue is the position of your tongue: Spread it sidewise, so that it gets into contact with the left and right inside of your cheek, and lift it a bit. This is nearly the same as pronouncing an English EEEE, only that the pitch is lower, i.e. something in your mouth (the front third of your tongue? don't really know, sorry) has to move a tiny, tiny bit down. And for this E, please ignore the thing with nearly closed lips or tipping them, that's only valid for O and Ö, not the E. Then an E should sound much more like a German light E. Another way to achieve the light E sound is to perform a slow transition from an English ee, like in bee, beeeee, to an ae sound like in English bed, beeeeed. At about one third of that transition, you should come across the sound of a light, German E. Once again, the spelling of a German word gives you no exact hint when to use a light or a dark E (like it's done in French). You have to learn it for every word. One example is Brezel, which is known as a pretzel in English (listen to forvo). The first E in Brezel is pronounced as a long, light E! Not at all like that short, sharp, ä-like sound in English. — Also, in all cases of an elongated E like in EE or EH, this is pronounced as a light E. |

| I | This is like an English EE or IE, simple as that. |

| O | Here we have again both a closed and an open variant. In the closed case, you can try to tip your mouth like for kissing or for a duck face or to say the word boot. The difference between this sounding like an "UH" and the closed O comes from a tiny difference in your tongue's position. This tipping is an exaggeration, you don't need it later, but I think it's a way to learn to produce these sounds. An example is the word Ofen (oven, listen to forvo). — The open case is the common English variant like in the word soft, but again, constant, straight, no diphthong like that English O-U, an example is the word offen (open, listen to forvo). |

| U | This is very similar to the English sound. Again, no diphthong, no leading Y to sound like YOU, no! Just like in the English word blue, it's straight, constant uuuuuu. Or take the English words boot or food. Try the word Zukunft (future) with a long U in the first place and a short one in second (listen to forvo). |

| Y | This is a vowel in disguise, in German just like in English. In German, it serves sometimes as a replacement for an I or an Ü, see there. The letter is read out as Ypsilon (listen to forvo). |

About Umlauts Now we get to the umlauts, the vowel variants with the two dots on top. This is not to be mixed up with the trema, that's some very different issue. Also the umlaut dots are NOT considered as "accents", the whole characters including the dots count as own characters. Historically the umlaut dots looked different: sometimes as a little e on top of the vowel, sometimes like a double quotation mark (") on top of the vowel. You can watch this together with additional information on [en-WP Germanic umlaut]. The umlauts are considered the dirty, fuzzy, or distorted variant of the respective vowel. That is especially interesting in the case of the Ä, which is practically identical to the pronunciation of the letter A in English. Thus English sounds a little dirty to German ears. Don't feel offended, it's just some weird coincidence. This text is about pronunciation. But let me here insert something about writing German text: If you come across an umlaut, and your keyboard does not provide one, there are several ways to solve this situation. Either you step down a little deeper into your computer and find one way to still type such exotic characters, on modern computers this is no feat anymore. Or in worst case, you can resort to replacing the umlauts by their base vowel PLUS an extra E trailing. So Ärger becomes Aerger, rösten becomes roesten, etc. But you never, NEVER, NEVER EVER are allowed to just omit the dots and write the naked vowels! This is a deadly sin, every day ruthlessly executed by many, many englishmen, and they will rot in hell for this slaughter! Again, please excuse my loud voice, but this is very depressing, when one has to see how others deprive your own loved language. Please note also the other way round: Whenever you see in a printed text a vowel A, O, or U followed bei an E, then the chance is near 100 % that this has to be pronounced as an umlaut. Especially in names, such forms of spelling occur. The most prominent example is our German poetry and author hero, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (pronounce him like Yo-hunn Volfgahng fonn Götha). His last name is definitely pronounced with a light ö umlaut. A slightly different issue is the history of some mister Böing, who emigrated from Germany to USA, there spelled his name Boeing by correctly transcribing the umlaut, and eventually began building famous airplanes. When a German sees this name and doesn't know a thing about airplanes, he might pronounce it like Böing, and from the above you find that that's not as wrong as it would appear initially. — One exception of this rule is again with names, especially of towns like Soest, Coesfeld, and Itzehoe, where the E after the O serves to mark an elongated vowel, as if the E were replaced by an H: "Westfälisches Dehnungs-E". Yet this is a very regional issue, not typical for general German. Another issue to mention are German crossword puzzles and similar puzzles. In all of them, by convention never ever a real umlaut does occur. They are always transcribed as a plain vowel plus an E. So again: Never just omit the umlaut dots, but transcribe an umlaut by its plain vowel followed by an E. Yet there is one exception: The German version of the Scrabble game (isn't that of American origin?) comes also with umlauts, which carry rather high point rates. Ok, the umlauts one after the other:

| Ä, ä, AE, Ae, ae | This sounds like a very dark E, or simply like the English A, without its trailing I diphthong. Take as example the word Ärger (annoyance, anger, listen to forvo). But the Ä also sometimes comes in a closed, light variant, sounding like the light E explained above. Example: Mädchen (girl, listen to forvo). (Hmm, I just realize that in the provided examples some speakers also pronounce this sample in the dark version. Try to focus on those using the light pronunciation.) |

| Ö, ö, OE, Oe, oe | This sound also exists in English, like in the words word, herd, or bird. Here we have again closed and open variants, like for the basic vowel O. The English sound of "word" represents the dark, open Ö. A German example is the word können (to can, listen to forvo). For the closed variant, again just close your lips and tip them like for kissing or a duck face, or to say the word boot, and the sound changes in the wanted way. — An example for the soft Ö is the German word for beautiful, schön, pronounced with a very long, smooth, soft, closed Ö: schööön (listen to forvo). If you correctly use this soft Ö, then the whole word actually sounds very beautiful, even more than its English translation because of its fewer consonants. If you pronounce it with the — for englishmen — more common open Ö, then it sounds harsh and ugly, fulfilling all prejudices about German pronunciation which exist. |

| Ü, ü, UE, Ue, ue | This is one of the major stepping stones for englishmen.

They simply cannot produce this sound. Why? I don't know. But hopefully, I can

provide some hints how to approach this issue. There are at least two ways: 1. Take the Y, use it as a vowel, like in the word system. Then stop at the Y letter and straightly and constantly elongate that sound: SYYYYYYYSTEM (same in German, listen to forvo). The Y here should serve as a rather good approach for a German Ü. 2. Begin with an English EEEEEEE (German IIIIII). Then keep your tongue unchanged, or do to it the same as proposed above for the light E, only close your lips and tip them like for kissing or a duck face, or to say the word boot. (Always the same procedure, this is a kissing seminar in disguise!) Also this should bring you near the wanted sound. Eventually try the words müde (tired, listen to forvo) or übrigens (by the way, listen to forvo). A funny aspect is that some Americans already pronounce the U sound in words like "food" already a bit in the manner of an Ü. To hear the plain, flat U sound, they have to use words like could or would. By the way: The sound of a normal car horn sounds a bit like an Ü for German ears. So when we want to imitate this sound, we write or pronounce it like tüt, tüt. Let's also mention that this Ü is not a German-only invention. The letter and its pronunciation is also used heavily in the Turkish and Finnish languages (together with the Ö umlaut). In French and Dutch language, even every plain letter U is pronounced like the German Ü; when they want to get a U sound, they have to resort to the OU diphthong, which is also known in English. |

4. Diphthongs

Diphthongs are pairs or triplets of letters, like "sh" or "ow" or in German "sch". In such diphthongs, letters can sound differently from the combined single letters.| ei, ai, ey, ay | The most frequent diphthong in German is the ei, which sounds basically just like the whole English word I. This is an exception from the claim that German is considered as a mostly "phonetic" language with tight concordance of spelling and pronunciation. Here, the E in ei is pronounced like a German A. Yet consequently, also the spellings ai, ay, ey exist and are used often in name variants. The most frequent family name in Germany is Meier, or Meyer, or Maier, or Mayer, respectively, and all are pronounced identically. So when some person introduces herself or himself to you, she or he will often add "Mayer mit A Ypsilon" to make the spelling variant clear (listen to forvo). |

| au | This is just phonetic, an A followed by a U, together sounding like the OW in the English word how or like the OU in the word about. Take as example the word Maus (mouse, listen to forvo). |

| eu, äu | This is not phonetic, but sounds more like the German vowels O and I put together, just like in the English word boy. So the word Europa (Europe) has to sound like OYROHPAH (listen to forvo). |

| ou | This does not occur in pure German words, but often in foreign lean words (see there) and is then pronounced like in French or English, as a plain U. |

| sch | This is exactly the same sound like the English SH, like in the word dish. |

| ch | This is also very difficult for English speakers. Again, some knowledge

of the Scottish accent may come helpfully into the game: Their Loch Ness

is the same sound, probably a bit more rough, but practically the same.

From the basics, you produce the sound by a very, very soft, toneless

hissing. Remember, it has to be very soft. To replace this diphthong just by

a K sound is not a solution, that's one of those points you immediately

unmask yourself as an englishman trying to speak German.

Yet, as in many languages, there are exceptions to the rule: In German words

like Fuchs (fox) or Luchs (lynx), the CH is pronounced like

a simple K. Exceptions are a sign for normal life. Hmm, do I see a pattern

here? CHS turns into an X? Honestly, I don't know, that's just a suspicion.

— Plus, in German there is never a leading T sound like in the English

words church (German Kirche, listen to

forvo)

or change. The number 6, German sechs (with a smooth first S, like the English Z), is a difficult example: Normally its CH is pronounced like a K, like in Fuchs. But when the CH is followed by a Z instead of an S, like in sechzehn (16) or sechzig (60), it is pronounced like a real CH: ZECH-TSEHN (listen to forvo) or ZECH-TSIG (listen to forvo), respectively. A special case occurs if the CH is at the start of a word or of a syllable. Then all chaos can break loose. In Hochdeutsch this will still be pronounced like standard CH, but in many regions of Germany, it will be pronounced as a K or even as a TSCH, just like in some English words like change. And some extremists even will pronounce it as SCH without the T. Take the country of China, spelled in German just like in English. You will find all the above pronunciations in different places of Germany, and not only in small areas there, listen to forvo. It's a problem, yet not too big, as everybody will still understand it. If you ask which other languages besides Scottish also have this sound, then Greek — at least the antique variant — may serve as an example. The letter Chi (Χ) is written like an uppercase X, but pronounced like the German CH. Also Spanish knows this sound, in some cases the J is pronounced like a German CH, an example is the town name Aranjuez. And not to forget Dutch, where a G is often pronounced like a German CH, only a bit more roughly. |

| ck | Simply a sharp K like in English. |

| ph | Like in English or French, this is often pronounced like an F. But watch out for syllables: E.g. the word Klapphaken (foldable hook) has the P in the first syllable and the H in the second, so they are pronounced separately. |

| st, sp | In some cases, these diphthongs are not pronounced with a sharp S, but with a very short and soft SCH (see above) for the S, the following consonant is pronounced normally. This is an issue heavily varying with the local dialects, some of them using a more explicit SCH, some using a normal S, but the hochdeutsche variant is that with the very short, soft SCH. Examples are the words Stuhl (chair, listen to forvo) or Sport (sport, listen to forvo). |

| H after a vowel, double vowels | Just like in English, this indicates an elongated vowel. |

| tion | (At the end of a word or syllable, like in situation.) In English, this is pronounced like SHON or SHIN. Yet in German, it's pronounced like zion or English TSEE-OHN, with a long, soft O (listen to forvo). |

| pf | This just does not occur in English. In German, it is pronounced just as written: Pferd, P-ferd (horse, listen to forvo). |

| kn | Unlike English, in German these two consonants are pronounced just as written: K-N. Example: Knopf = K-nopf (button, listen to forvo), not "nopf". |

| th | Unlike English, in German these two consonants are pronounced like a simple T (forget the H here). There is just no such tongue-injuring sound like in English. |

5. Ordinals, date, time

First let me point out to those who are not already aware of this special quirk with German pronunciation: In numbers beyond 10, we pronounce first the ones value and only then the tens value, the bigger factors remain unaffected, luckily. Example: 23 is dreiundzwanzig, 361 is dreihunderteinundsechzig (or should I spell it drei hundert einundsechzig? Nah, this is about German). – By the way, are you aware that English also has a bit of this feature, for the numbers from 13 to 19, the "teens"? Ordinal numbers - Now, where English counts like 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, etc., German just uses a simple dot: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., etc. So when you see a dot after a number, you better check whether this is the end of a sentence or an ordinal. In the latter case, it's pronounced as erster (or erste/erstes/..., all those declinations, yes, German is very complicated here), zweiter, dritter, vierter, fünfter, etc. All these are referred to as "ordinals". This also affects royals. When King Charles III is mentioned in German, you normally find another dot after the "III": A sentence like "Charles III likes parades." becomes translated "Charles III. liebt Paraden." This is pronounced like "Tscharls der dritte liebt Parahden." ("der dritte" meaning "the third"), using the dot as indicator for an ordinal, not as the end of the sentence. Dates - This is also important in the case of dates. You know perhaps already, that in Germany the format dd.mm.yyyy is used, or in German tt.mm.jjjj for Tag, Monat, Jahr. After the information from the preceding paragraph, you will understand that the dots are not just separators, but they work to mark ordinals. Thus a date is also often written with spaces, like dd. mm. yyyy. As an example, the 15th of January (never "January, 15th" in German) is written as 15. 1. 2016 or 15.1.2016 or 15.01.2016 with zeros as fillers. It's pronounced as fünfzehnter erster Zweitausendsechzehn. Due to the dots serving for ordinals and not as simple separators, alternative spellings like "15/01/2016" or "15-01-2016" like in Britain are very unusual in German. It just wouldn't make much sense to a German reader, we need those dots there. The year is in most cases pronounced as the full figure: 1981 = neunzehnhunderteinundachtzig, 2022 = zweitausendzweiundzwanzig. Only now in the new millenium, you often hear the shorter variants like zwanzigzweiundzwanzig. Times - The latter issue is different with clock readings. They are not written nor pronounced as ordinals, thus a wide variety of separators can occur in German texts. There is no hard standard, sometimes pure chaos can occur, you have to be ready for any possible combination. An American time of "3.11 pm" can appear in German as 15.11 Uhr, or just 15.11, or 15:11 Uhr, or 15:11, or 1511, plus a couple more. The pronunciation is always the same: fünfzehn Uhr elf, or also more similar to American use drei Uhr elf nachmittags. As we don't have these am/pm shortcuts in German, the long winding vormittags or nachmittags or abends is not a very attractive alternative to the 24-hour wording. Only when it's totally obvious what is meant, the short form of drei Uhr elf or elf nach drei (11 past 3) is used also in the afternoon. In Germany, the 24-hour time is quite common, so it's a normal option. Yet nobody here identifies this as "military time", it is not at all connected to military here. And please note that in German, you don't say something like "three hundred hours", no hundreds involved here ever. When you speak of a very exact timing and would use "11 sharp" or "11 precise", this will sound in German "Punkt 11 Uhr". There are special pronunciations for quarters and halves of hours. They are very similar to English, but not quite. A time of 03:30 Uhr is not half past 3, but halb vier. So the outlook is here for the next hour. When it comes to the quarter hours, there is a regional variation. In the northwest they pronounce 03:15 Uhr as viertel nach 3 Uhr (practically like in English), but in the southeast (including Berlin, there is the same diagonal separation line as mentioned below with Samstag/Sonnabend) as viertel vier (a quarter of the hour leading to 4), again with the outlook to the next hour. And 03:45 Uhr is pronounced in the northwest as viertel vor 4 (quarter to 4) and in the southeast as dreiviertel 4 (three quarters of the hour leading to 4). Fractions - When we talk about halves and quarters, let's also look at all the other fractions. Where in English a fraction of 1/5 is pronounced as one fifth, in German there is a "-tel" appended to the denominator: ein fünftel. With the only exception of the already mentioned halves for 2 as the denominator, this applies to all fractions, e.g. 14/27 is pronounced as vierzehn siebenundzwanzigstel. Ok, there is also an S inserted to make pronunciation easier. This is called a "[de-WP Fugen-S]" ("gap S"). More on Dates - But let's get back to dates: A calendar in Germany looks a little bit different from one in USA. A week in Germany starts with a monday, not a sunday like in USA. The sunday is part of the weekend, and so it cannot logically be the start of a week. — The weekdays are named a bit differently, but that is not the issue here. I only want you to note the fact that the weekdays are commonly abbreviated with only two letters and not three like in USA: Mo = Montag, Di = Dienstag (tuesday), Mi = Mittwoch (wednesday, middle of the week), Do = Donnerstag (thursday), Fr = Freitag, Sa = Samstag/Sonnabend (saturday), So = Sonntag. When to say Samstag or Sonnabend depends on the region. Germany is roughly divided by a diagonal line into a northwestern part, where they say Sonnabend, and a southeastern part, where they say Samstag (same division like above for the quarter hours). For business people, an appointment is often referring to a certain calendar week. But please be aware that these are counted again differently in Germany vs. the USA: In the USA, every 1st of January is in the 1st calendar week of the year, in Germany it isn't necessarily! In Germany, the first calendar week of a year is the week which contains at least 4 days of the new year. So if the 1st of January falls onto a friday, then it counts for the last week of the previous year, and the first calendar week only starts with the 4th of January on the following monday. And please be aware that this offset will continue through the whole following year. So you will have to fix WHICH or WHOSE calendar week you are going to rely on. You risk an offset of a whole week when meddling this up. Special cases - In the case where high precision is necessary when reporting some numbers from one person to another, you want to avoid mixups. As the figures zwei (2) and drei (3) sound rather similar, the speaker often replaces the zwei by a zwo (TSVOH). A bit more rarely, the fünf (5) is replaced by füneff (just like that "fiver" in English). — Similarly, when pronouncing dates, the names of the months Juni (june) and Juli (july) are critical to distinguish. The solution is to pronounce Juno (YOONOH) instead of Juni and Julei (YOOLYE) instead of Juli. Numbers with many digits - When you come across numbers with many digits, you will note that the thousands and decimal separators are just exchanged, and the latter is also pronounced as "Komma": 123.456.789,123.456. Note that in Swiss-German texts, the thousands separator is often an apostrophe: 123'456'789,123'456. For really big numbers beyond a million, you will also have to handle the completely different naming schemes for billion (Milliarde in German), trillion (Billion in German), and so on. See [en-WP Long and short scales] or the German equivalent [de-WP Lange und kurze Skala] for insight on this really complicated matter. Those big factors are also abbreviated differently in German: A million is written as Mio (NOT just M!, but pronounced "Million"), a "Milliarde" as Mrd (of course not a B), and for the even bigger factors, there are no abbreviations common. By the way, the smaller factor 1000, German tausend, is sometimes abbreviated as a simple T. Only scientists or engineers use the k, with the exception of the units km (Kilometer) and kg (Kilogramm), which are universally used. There are also shortcuts possible: When a number contains a 1xx or 1xxx part, you can pronounce it either like einhundert..., eintausend... or shorter like hundert..., tausend.... The first version is the more precise one, but in many cases you can get around with the shorter one without problems. You remember the remarks above about the German method to pronounce first the ones value of a number and only after that the tens value? Well, this also occurs in the big numbers, multifold. Example: 864.973 (note again the dot as the thousands separator) is pronounced as achthundertvierundsechzig tausend (und) neunhundertdreiundsiebzig. Decimals and Units - Last not least let's mention the pronunciation of numerical values with decimals and units. The good news is that this is very, very similar in German and English. When you ask someone how tall he is, he will perhaps answer "ein Meter zweiundachtzig" or short "eins zweiundachtzig", which means 1,82 m. Or prices: There you will hear "Das kostet drei (Euro) vierzig" for 3,40 Euro. Surprisingly, this is not common for some other types of values, e.g. a battery marked with "2.3 V" will always get pronounced like "zwei Komma drei Volt". I can't really tell where it is this way and when the other. Just listen to the people. When it is about lengths, Americans are also accustomed to speak of fractions of an inch, half, quarter, eighths, etc. In German you speak about a "halbe(n) Meter" (half) or a "viertel Meter" (quarter), but never for the smaller units. Same with clock timings: "halbe Stunde" or "Viertelstunde" (yes, this is one word, while the "halbe Stunde" never gets bound together, don't ask me why) is common, but no smaller fractions. — There is one special case: The fraction 1 1/2 (1.5 or 1,5) is pronounced in German as "anderthalb". By the way, we are in Europe. You are supposed to use the metric system, no inches, no feet, no miles, no Fahrenheit. It's Meter and "Grad Celsius" (the C pronounced like a TS). We have the "Kilogramm" and the "Pfund" which is not at all identical to the American pound, but exactly 500 g, i.e. exactly half a kg. And when it comes to fuel consumptions of cars, we express this as a value of "x Liter pro 100 Kilometer", which can be derived from your MPG (miles per gallon) value by dividing the number 236 by your value and the other way round. So, if a German tells you his car only consumes "4 Liter pro 100 Kilometer", you calculate 236/4=59, and the latter is the same consumption in MPG. And the other way round: Given a value of 59 MPG, you calculate 236/59=4, and this is the value in liters per 100 km. Same with speeds. We don't use the kph abbreviation for km/h like in USA. We use always this km/h and pronounce it as Kilometer pro Stunde. You will also often hear the term "Stundenkilometer" instead, yet this is considered a bit sluggish and is not recommended. There are a couple more complicated units, in parts obscure, others as part of the metric SI system:- qm for Quadratmeter, m², square meters

- qcm for Quadratzentimeter, cm², square centimeters

- ccm for Kubikzentimeter, cm³, cubic centimeters

- ar for Ar, 10 m squared, or 100 m² (no acres seen here far and wide)

- ha for Hektar, 100 m squared, or 10000 m²

- s, sec, sek for Sekunde, second, the latter two spellings are a bit obscure

- h, Std for Stunde, hour

- PS (pronounce as PEH-ESS, with a light E for the PEH), Pferdestärke, horse power

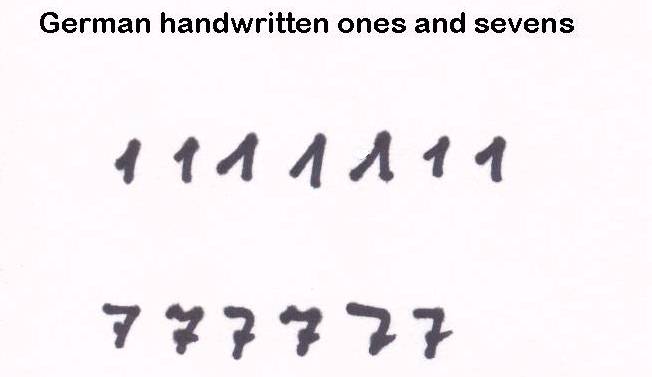

| Handwritten numbers - This is a severe issue! There was once an accident with several fatalities, because some English (or American) artillerist in a maneuver presentation misread the target coordinates which a German observer had passed him on a handwritten note. It was said that he read a seven with that extra horizontal line as a weird form of a four. In German handwriting, the seven is practically always written with an extra horizontal line, see the examples on the side. — And the one is practically always written with an ascending line on the left, which is found in English only in print, so that an English reader can confuse it with a seven! |  |

6. Lean words

Like in English, the German language has adopted many lean words from other languages. In earlier times more often from French, in recent times more often from English, plus of course many other contributions from other sources. Unlike French, we in Germany tend to pronounce such words similarly to the pronunciation in their home language. Yet this is just a trend, not an absolute rule. In cases, you will find either variant, and I cannot state a rule when to use which pronunciation. Many of those older imported words have changed their spelling over time. The French "bureau" became "Büro" in German, with practically the same pronunciation, but now after normal German rules. Especially for verbs, they often get handled like German verbs. Example: English: to post, posted, posted. German: posten (with the o pronounced like in English like a German "O-U"), postete, gepostet. (Sometimes you will find a spelling like "geposted", but that's considered a dirty, false errant: Starting with a German "ge-" and ending in an English "-ed", that's just not it.) Just like a regular verb in German.7. No word bindings

In English, you bind words together when it fits. "It is" is pronounced like it were spelled "Itiz". This does not happen in German! There is always a little pause between separate words, the official term is "glottal stop". Yet this should not necessarily lead to a staccato-like pronunciation. But you know that we love to spell words together like Damenhandtasche (lady's hand bag, purse), and inside such compounds, the words will be pronounced together. But then consider the issue of the next chapter.8. Syllables

One potential pitfall concerns syllables. Let me state an example: The German word bisschen (a bit of) does NOT contain the SCH diphthong! No, it contains the syllables biss- and chen (the latter marking a diminutive), and so they are pronounced separately. Also the word Klöpschen (small meat ball) carries this diminutive, so that the syllables Klöps- and chen have to be pronounced separately. Same with compound words like Buchseite (book page), which is pronounced like Buch-Seite, so the CHS inside does not get changed into an x like with Fuchs. And also the word Autounfall (car accident) does not contain the diphthong "ou", but is pronounced as Auto-Unfall. Another case is a verb like bauen (to build), which does not contain the diphthong or umlaut "ue", but is pronounced bau-en.9. Gendering

This is a very recent, extremely controversial issue. As you perhaps know, in German we are used to adapting nouns to clearly show the gender of the person or animal this applies to. Example: Whereas in English you talk about "teachers", be they male or female, in German we have male "Lehrer" and female "Lehrerinnen" (both plurals). Another example, where it's even rather similar in English and German is English "lion" vs. German "Löwe", but for females English "lioness" vs. German "Löwin" (here only the singular forms). Now in German, the male form like "Lehrer" serves also as the general name for the position, like in English. Yet this is for some time no more well received among feminists, and so spellings were tested to show both genders. There were approaches using an asterisk or slashes or brackets or an internal capital I (a "Binnen-I", like in "LehrerInnen"). The currently dominating version is a spelling with a colon inside the words. In our example this shows up like "Lehrer:innen" (plural). You recognize from my wording that this is still a moving target. And here we come to the point of this whole text, which is about pronunciation. There is the intent that this "gendered" spelling should also be audible through some adapted pronunciation. The solution is that at the place of that colon, the speaker inserts a pause of a blink of an eye, experts call this a "glottal stop". As an example, let's consider a group of all female teachers, in German you can refer to them along the normal syllables as "Leh-re-rin-nen". If their gender is mixed or unknown, you now better speak of "Leh-rer-in-nen". Please note the fine difference. This is an exciting issue when you realize you are watching a change in your language where similar changes in the past took decades or even centuries, and now this happens during your lifetime. When I was young, there were already smaller changes: The term "Fräulein" for a young and/or unmarried woman was changed to "Frau" to avoid discrimination. And in science, the term "Oxyd" was changed to the more international form "Oxid". Let me state again that this gendering is highly controversial. In some (right-extremist) circles you will receive boos when speaking this way. But the general trend appears to follow the wishes of the female half of our population. By the way: Here abroad in Europe, we do not (yet?) care or discuss "pronouns" which seem to be a big issue in USA currently. In case of doubt, we simply ask the person how he/she wants to be addressed, and if we are polite people, we will follow this wish. As we still have non-discrimination legislations, companies are urged to use "m/w/d" (for männlich/weiblich/divers, male/female/diverse) in job offerings.10. Reverse approach

Let's try a reverse approach by showing how some English words would have to be spelt, so that some German reader would pronounce them correctly, just by applying his normal, German pronunciation rules. This of course won't work with all English words, but there are some which can perhaps lead to a bit of enlightenment. Let's start with the English word "ouch!", when you suddenly feel some pain. A German will emit the exact same sound, but will spell it autsch! to achieve this exactly identical pronunciation. When you look closer, you will recognize the leading diphthong AU, the T is needed to reproduce a part of the English CH sound which does not exist in the German version, and finally the SCH, producing the same sound as the English SH or the trailing part of the English CH. This English CH with a leading T in its pronunciation is more obviously visible in the English word "church". To produce this sound, you would have to spell it Tschörtsch (with an open, dark Ö) in German. That looks funny, and it also sounds funny to German ears. How does a cat sound? It says "meow". In German, it is the same sound, but spelled "miau", simply following German pronunciation. Then there is the English word "ice". Again, the translated German word is pronounced 100 % identically, but is spelt "Eis". It starts with the EI diphthong, the S is the phonetically logical end. A more fun example is the English word "why". At school, our English teacher told us, we could easily pronounce this when we just chain all the five normal vowels (pronounced German) together in the appropriate order: U-O-A-E-I. Hey, it really works! Let's talk about the tiger, an impressive, elegant animal. The German word for it is spelt identically, but pronounced differently, with a long "EE" for the I in second place. To achieve the English pronunciation, you would have to spell it "Teiger" for a German, featuring the EI diphthong. Ok, the R will still differ heavily, there's no way to indicate this in German spelling. Similarly to the I in "Tiger", our capital city Berlin is pronounced with a long, light I. This name ending in -in is typical for many names in the eastern part of Germany with some Slavic background or history, and all are pronounced with that long, light I, like in English "teen". Stepping down from the tiger to its smaller relative, the cat. How does a cat sound? Yes, "meow". And in German, the sound is 100% the same, but the spelling has to be adapted: the "me" becomes "mi" in German, and the "ow" becomes "au", together "miau", sounding exactly like its English counterpart.11. Hard exercise

When you really are out for a challenge, why not try German tongue twisters? These are Zungenbrecher (tongue breakers) in German. You find several of them in the German Wikipedia: [de-WP Zungenbrecher]. There you find also a number of audio files from the examples, see also the Commons files. The two most common Zungenbrecher plus one newcomer I'll mention here:- Fischers Fritz fischt frische Fische, frische Fische fischt Fischers Fritz. (Fisherman's Fritz fishes fresh fish, fresh fish (are) fished by Fisherman's Fritz.)

- Blaukraut bleibt Blaukraut und Brautkleid bleibt Brautkleid. (Red cabbage stays red cabbage and wedding gown stays wedding gown.)

- Barbaras Rhabarberbar (Barbara's rhubarb bar; most recent one from early 2024, see also on [YT])

12. Example pronunciations via Internet

When you want to hear pronunciation samples of a certain single word, the web site forvo.com can serve you. You type a word, and if it is found in the internal list of available samples, you are offered even a number of various pronunciations by different speakers. Click on a blue triangle, the play button, to start the sample. A quite different approach is the use of browser add-ons for a feature called text-to-speech. With such a tool installed in your browser, you e.g. mark a word or a whole sentence, click a button and hear it pronounced in the language provided by the tool. (There are different ways these tools work, some will read out the whole web page to you, others only selected passages.) One such tool, which automatically detects German text and reads it out loud, is "Read aloud" (for Chrome or FireFox browsers). There are a lot more available, just look around in the add-on search lists for one that fits your needs best. — Of course, such tools are only applicable when you have loaded a German-language web page, they do not translate. Another source for well-pronounced German speech are TV news, which can be found on the net. They have typically their own web sites. The most reknown being tagesschau.de. The "second program" named ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen) comes as zdf.de/nachrichten. Both offer a special service in that some clips (not all) come with sub titles, not translations but the German text in typing. To get to these clips is a bit tricky: In the top right corner you find a Suche (search) field. Type there Untertitel (sub titles) and send this. You get back a page with those clips listed which come with sub titles. When you start one of them, you will have to find the "UT" button (Untertitel, at tagesschau) or the Spracheinstellungen anzeigen (show settings) button (at ZDF) in the bottom right, which among others offers you to switch on the sub titles. A bit tedious, but eventually it works. There is of course THE standard for the German language, the Duden. (This is for German what Webster's is for American English.) It comes with additional information about grammar issues and pronunciation via phonetic spelling.Not exactly pronunciation, but if you are looking around for a dictionary besides Google services, you might take a look at Leo which serves me well.

And a last time talking about a dictionary: When it comes to special terms from science or technical stuff, then I use Wikipedia! Yes. Just invoke your English Wikipedia with the word in question and then look down in the list of "nnn languages" at the top right: There you find the parallel articles about the same issue in several other languages. And as German is the second biggest variant of Wikipedia, chances are high that you will find there (ok, you need to select "Deutsch" as language) an article under the title of the searched translation of the English term. And Wikipedia also often offers phonetic spelling information for pronunciation.

13. Finnish!

The whole time I searched my memory for another language with similar pronunciation rules, besides Hawaiian I mentioned at the beginning. Now finally I found one: Finnish! It is pronounced way more roughly than German, but in principle in the same way, also with all those umlauts. From that side no problem for a German tourist there, but when it comes to the vocabulary, that's quite a different problem, and a big one.14. tl;dr

- No need for staccato-like pronunciation, German can sound as smooth and soft as others.

- Yet no automatic binding between words.

- Vowels to be pronounced constant and steady, not as diphthongs.

- Differences between open and closed vowels are to be obeyed.

- Pronunciation of umlaut vowels needs exercise.

- Consonants L and R differ heavily in intonation compared to English.

- TH is pronounced like a simple T, no English-like TH sound.

- There are own diphthongs like EI or EU to be handled.

- Syllable borders may collide with supposed diphthongs.

- Numbers and clock readings need separate attention.

15. Last words

One last gag about German and its pronunciation. The German word for a cold sickness (I caught a cold) is Schnupfen. This is indeed rather stressful to pronounce. BUT ... As soon as you really caught that cold, you are finally, definitely unable to pronounce it correctly. So much about the logical German language. See you.↑ Seitenanfang/Top of page / DSGVO, © Copyright Dr. Peter Kittel, Frankfurt/M, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025